Ionic order after Palladian. Basic rules of Palladian and Vignola order systems. Development of the architectural order as an artistic and constructive system

ARCHITECTURAL ORDERS ACCORDING TO VIGNOLLE

METHODOLOGICAL GUIDE

TOMSK - 2008

Polyakov E.N. Architectural orders according to Vignola: Methodological manual. / E.N. Polyakov - Tomsk: Publishing house of the Tomsk State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, 2008. - 124 pp., table. 8, ill. 77.

Reviewer: Ph.D. architect, associate professor L.S. Romanova

Editor T.S. Volodina

The methodological manual contains information about four types of architectural orders - Tuscan, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. It was about them that Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola wrote a treatise in 1562, which became a visual aid for connoisseurs and admirers of ancient art. This publication includes text, illustrative and tabular material about these modular systems. Here are the rules for graphically constructing parts and details of orders, drawings, tables, illustrations, a terminological dictionary and a list of references on this topic.

The methodological manual is intended for students of the Faculty of Architecture in specialties 270301 (“Architecture”), 270302 (“Design of the Architectural Environment”) and 270303 (“Restoration and Reconstruction of Architectural Heritage”).

Published by decision of the methodological seminar of the Department of Theory and History of Architecture No. 4 of March 9, 2008

Approved and put into effect by the Vice-Rector for Academic Affairs V.M. Dzyubo

from 01.09.2008

Signed for seal

Format 60´90/16. Offset paper. Times typeface, offset printing.

Academic ed. l. 1.9. Circulation 500 copies. Order No.

Publishing house TGASU, 634003, Tomsk, pl. Solyanaya, 2.

Printed from the original layout in the TSASU Department of Public Education.

634003, Tomsk, st. Partizanskaya, 15.

CONTENT

Introduction………………………………………………………………………………5

1. GENERAL PROVISIONS ………………………………………………………………7

1.1. Order system………………………………………………………. 7

1.2. Development of the order………………………………………………………7

1.3. Order structure………………………………………………………12

1.4. Architectural breaks (profiles) ……………………………………………………….. 17

2. CONSTRUCTION OF ORDERS………………………………………………………. 18

2.1. Tuscan order …………………………………………………………… 22

2.2. Doric order……………………………………………………………31

2.3. Ionic order……………………………………………………………47

2.4. Construction of the Ionic Volute.………………………………………….. 57

2.5. Corinthian order……………………………………………………….. 62

3. CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLONNADE …………………………………………………… 74

4. BUILDING AN ARCADE ………………………………………………………. 83

5. GENERAL RULES FOR CONSTRUCTING ORDER DETAILS …………………... 96

5.1. Construction of flutes …………………………………………………….. 96

5.2. Construction of a simple column entasis (Tuscan,

Doric) order……………………………………………………… 97

5.3. Construction of a complex column entasis (Ionic,

Corinthian) order………………………………………………………97

DICTIONARY………………………………………………………………………………100

LITERATURE ………………………………………………………………………………………… 123

INTRODUCTION

The educational work “Architectural Orders according to Vignola” is one of the stages in improving the graphic skills of junior architecture students. In addition, students are introduced to the most popular system of constructing architectural orders, developed in the mid-16th century by the Italian architect Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (1507–1573). The skills acquired during the work will help them better understand the compositional features of classical architectural monuments.

The work is done in pencil, ink or in one of the computer graphics programs (in agreement with the consultant) on a stretcher measuring 50x75 cm. The project includes the following components:

· name of the project in Russian or Latin (for example, “Architectural orders according to Vignola”);

· comparative analysis of four Roman orders (“Architectural orders among the masses”);

· detailed construction of two orders - simple (Tuscan or Doric) and complex (Ionic or Corinthian) in incomplete or complete versions;

· the most characteristic detail of one of the orders (a fragment of an entablature, a capital, a column base, etc.);

· one or two options for the practical use of selected orders in arcades and colonnades (full or incomplete orders).

Before performing graphic work, students take an academic test on architectural orders, which requires knowledge of the terminology of orders and the general rules for their construction.

When writing this work, we were guided, first of all, by the original - the treatise by D.B. da Vignola's "Rule of the Five Orders of Architecture".

According to the writer, his research was limited to the “architectural decorations” of five ancient Roman orders - Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Utyi and composite (composite). Having studied and measured many ancient monuments, the author of the treatise came to the conclusion that “those of them that, according to the judgment of the majority, seem more beautiful and show greater grace to our eyes, also have certain definite and less complex numerical relationships and proportions; not only that each smallest division of them measures larger divisions, dividing them into a certain number of parts based on prime numbers ... ".

Based on this conclusion, Vignola developed his own system of mathematical proportioning of ancient orders, guided “exclusively by one arbitrary measure called module and divided in each order into a certain number of parts.” The author of the famous treatise especially emphasized that he wrote it “exclusively for his own needs, without putting other purposes into it.” However, its simplicity and brevity appealed to “many gentlemen who want to learn without much difficulty to understand the entire field of art related to these decorations.” Therefore, Vignola’s work was translated into many European languages and turned into a publicly accessible “cheat sheet” for numerous fans of the art of the Italian Renaissance. The book had a huge influence on the everyday architectural practice of Europe in the 17th – mid-19th centuries.

Vignola wrote his work in 1562 in Rome. He dedicated it to his patron and regular customer - Cardinal Alexandro Farnese (1520–1589), grandson of Pope Paul III: “I, my Most Serene and Most Worshipful Master, could... present you with this little work so that it... could be passed on fearlessly from hand to hand, staying under the shadow of your great patronage; ... it belongs entirely to you, and since I am involved in it no more than a simple worker, all that remains for me, relying on your kindness and despite the smallness of this fruit, is to most respectfully hand it over to you, trusting that the great Lord accepts our lowly labors and rewards them as great, if only they stem from great zeal and purity of spiritual motives, and that the earthly rulers, no matter how insignificant the plant found in their gardens, still, although not equal to the more noble ones, by chance they will love him too, for the sake of his uniqueness..."

For his “lord and special patron,” the architect completed a design for a country palace with a round courtyard, in which a new system of proportioning architectural elements was tested (Fig. 1).

Rice. 1. Project of the Palace of Cardinal A. Farnese Cancelleria, ser. XVI century (author – D.B. da Vignola):

a – general view with a section; b – main entrance portal

According to A.G. Gabrichevsky, “The Rule of Five Orders” cannot be considered either a textbook, or, especially, a guide for design, since Vignola considers the order as a completely abstract mathematical system that does not take into account either the absolute dimensions of buildings or the perspective distortions that inevitably arise when the size of buildings increases : “He couldn’t believe that these proportions are suitable for any absolute value and that they can be mechanically increased or decreased without distorting their meaning...”. At the same time, no architect can ignore Vignola's treatise if he wants to understand the history of the classical heritage in European architecture, from the Renaissance to the present day.

GENERAL PROVISIONS

Order system

Architectural order(from fr. Ordre – system, structure, order) – artistically

a meaningful system of proportional relationship between load-bearing and supported elements

post-beam design

The order system was first encountered in the architecture of Ancient Greece in the 7th century BC. Until this time, in the history of architecture, certain forms of the post-beam system were known (Ancient Egypt, Achaemenid Iran, Syria, etc.), the basis of which was racks (pillars, columns) and beams , bearing the weight of the ceiling (Fig. 2).

Rice. 2. Hypostyle hall of the Temple of Isis on the island of Philae, 2nd century. BC (A);

reconstruction of the Achaemenid palace (apadana), 6th century. BC (b)

In the architecture of Ancient Greece and Rome, mathematical patterns were discovered in the dimensional relationships of the elements of this post-beam system, artistically expressive forms corresponding to this design were found, and universal methods for its practical implementation in various buildings were developed.

In the cult architecture of classical Greece (5th–4th centuries BC), this structural scheme was artistically processed to such an extent that it turned into a universal architectural “module”, equally suitable for use in buildings for a wide variety of purposes (Fig. 3) .

Rice. 3. Doric order. Entablature of the Parthenon (architects Ictinus and Callicrates, 5th century BC):

a – reconstruction option; b – current state

Order development

The development of the order followed the path of improvement and complication of the proportions of its parts and their architectural and decorative processing. In the ancient architecture of Greece, the main variants of orders developed - Doric , ionic And Corinthian.

Rice. 4. Tuscan order. Temple in Orvieto (5th century BC). Reconstruction

In ancient Rome, along with Greek models, new types of orders were widely used - Tuscan (temple in Orvieto, early 5th century BC) (Fig. 4) and composite (triumphal arch of Emperor Titus, 1st century) (Fig. 5).

Rice. 5. Composite order. Triumphal Arch of Emperor Titus in Rome (1st century):

a – general view (current state); b – capital

Order systems for a long period retained a leading compositional role and varied widely in the architecture of different eras and styles (Renaissance, Baroque, classicism, neoclassicism, Soviet classicism, etc.). The traditions of the order in original interpretations are also used in modern architectural practice (industrial classicism, postmodernism, etc.).

The order became widespread in the architecture of the Italian Renaissance (Renaissance). The heritage of antiquity in Italy was almost never forgotten, even in the Romanesque and Gothic eras. And during the Renaissance, ancient traditions became especially popular. This was facilitated by those found at the end of the 15th century. books by the Roman architect Vitruvius, who lived in the second half of the 1st century BC. In his works he outlined the foundations of the theory of architectural orders. They give the rules for constructing orders, using as a dimensional module lower diameter of the column.

The treatises of Vitruvius are carefully studied in the 15th–16th centuries. and on their basis treatises by S. Serlio, V. Scamozzi, L.B. Alberti, A. Palladio, D.B. yes Vignola. All of them began their architectural education with measurements and excavations of ancient buildings, and this was reflected in their literary heritage.

However, Vignola’s treatise “The Rule of the Five Orders of Architecture” became the most understandable and, as a result, the most attractive for architects. An equally popular theoretical work was “Four Books on Architecture” by Andrea Palladio. These two studies, based on a thorough study of antiquity, served as the theoretical basis for many architectural works. In these guidelines we will consider only the architectural orders described and studied by D.B. yes Vignola.

There are four main types of orders. These are Tuscan, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. All of them, to one degree or another, differ from each other in the degree of architectural and decorative elaboration. The fifth type of order – composite (“complex”) – is considered to be a composite of the Ionic and Corinthian orders (Fig. 6).

Rice. 6. Five orders from Vignola’s treatise (sheet III)

Order structure

An architectural order consists of three parts: the main part of the order is Column , the second part, located under the column, – pedestal , the third part, located above the column, – entablature .

Orders are divided into complete and incomplete.

Full order consists of 19 parts, of which 4 parts are on the pedestal, 12 parts on the column and 3 parts on the entablature (Fig. 7, a).

Incomplete order consists of 5 parts, of which 4 parts are on the column and 1 part on the entablature (Fig. 7, b). The pedestal is a part that can be excluded from the order, all other parts are mandatory.

Rice. 7. Main options for architectural order: a – complete; b – incomplete

Examples of the practical use of full and incomplete architectural orders are shown in the photographs below.

1.3.1. Entablature– the upper carried (supported) part of the architectural order. It consists of three parts: architrave, frieze and cornice.

Architrave– the lower part of the entablature, its main load-bearing part. It consists of stone blocks that span the span between the columns.

Frieze– the middle division of the entablature, which is a wide belt, on which, as a rule, decorative panels, relief or high-relief images are placed.

Cornice- the upper part of the entablature. In all orders it has three parts: supporting, hanging and crowning. The hanging part of the cornice has tearstone or teardropper, on the lower surface of which there is a special recess (“removers”) that serves to drain rainwater from the building.

1.3.2. Column– the load-bearing element of the order (or its middle part) also has three main components: the base of the column, the fust (or trunk, rod) and the capital.

Base columns (Greek) foot) - the lower part of the column, forming the base for its trunk. The base has three parts - a shelf, a torus (or shaft) and a plinth. Plint It is a square slab in plan, and the torus is round, with rounded ends.

Fust The column is a round column, somewhat thinning towards the top (from 1/3 of the height of the column). This thinning of the column, following a slightly convex curve, is called entasis. In all canonical orders, except Tuscan, the fust is processed by vertical, curvilinear in horizontal section recesses, which are called fluted.

Capital columns (lat. Head) completes the fust. It serves as a transition element from the trunk (vertical support) to the entablature (horizontal supporting part).

Upper part of the capital - abacus or abacus(Greek board) is a square slab that directly distributes the load of beams to columns. Below it there is a round part in the form of a quarter shaft (see section 1.4. Architectural breaks), which has a non-trivial name - echinus(Greek hedgehog). Placed under the echinus neck, which is, in essence, a continuation of the column core, but separated from it by a small profile.

1.3.3. Pedestal– the supporting element of the order (or its lower part) consists of 3 parts: plinth , chair And cornice pedestal. The base is sometimes called base or plinth pedestal.

All components and elements of the architectural order are shown in Fig. 8.

Rice. 8. Structure and components of the order

BUILDING ORDERS

All sizes in orders are determined using module . For Vignola, the module is equal to the lower radius of the column and is divided by 12 in simple orders desk (parts), and in complex ones - for 18 desks.

There is a very important rule in the construction of architectural orders - weightlessness rule . It lies in the fact that the upper parts of the architectural elements should not be wider than the lower ones. If the upper part has a bottom extension in the form of a base, then the width of the lower part under it should be the same as the width of this base. Cornices and capitals should not take any load on their protruding parts. That is, the width of the pedestal under the column should be equal to the width of the bottom of the column base; the width of the architrave stones should be exactly equal to the upper diameter of the column trunk, without at all burdening the overhang of the capital.

All main sizes of orders according to Vignola in desks are given in Table 1.

In Fig. 10–11 presents a component of the course work - “Warrants among the masses”. One of these options (“with the same module size” or “with the same order height”) is displayed on the tablet.

Rice. 10. Orders in masses (option with the same module size)

Rice. 11. Orders in masses (option with the same order height)

Tuscan order

The birthplace of the Tuscan order is Etruria (the modern province of Tuscany in Northern Italy). Here it developed in the 6th–4th centuries. BC According to Vitruvius, the column of the Tuscan order is characterized by a smooth, sharply tapering trunk on a rough round base. The trunk ends with a “spread out” echinus and a high abacus, which with their total height “often exceeded the upper diameter of the column trunk.” Even the ancient Romans believed that Tuscan columns “should be in the lower part as thick as a seventh of their height, and the height should be equal to a third of the sacred site...”.

This order is the simplest in its details and forms, but at the same time the heaviest in proportions. Therefore, in some literary sources he is associated with the image of an old man (Fig. 12).

Rice. 12. Statue of Jupiter-Fulgurator (a); detail of the Tuscan order according to N.I. Brunov (b)

In Fig. 13–18 show the main details of the Tuscan order that need to be depicted on the tablet - entablature, capital, column base, pedestal.

Table 2 shows the main dimensions of the Tuscan order profiles in desks. The dimensions of the protrusions are given from the axis of the column. For ease of figurative perception, they are written from top to bottom - from the top of the entablature cornice to the base of the pedestal.

Rice. 13. Entablature and capital of the Tuscan order from Vignola’s treatise (folio VIII)

Rice. 14. Tuscan order: entablature, capital

Rice. 15. Tuscan order: entablature, capital

Rice. 16. Column base and pedestal of the Tuscan order from Vignola’s treatise (sheet VIII)

Rice. 17. Tuscan order: column base, pedestal

Rice. 18. Tuscan order: column base, pedestal

Table 2

| Profiles | Height in desks | Protrusion from the axis in the desks |

| 1. Entablature | – | |

| 1.1. Entablature cornice | – | |

| Quarter shaft | 27,5-23,5 | |

| Roller | ||

| Shelf | 0,5 | 23,5 |

| fillet | 23,5-22,5 | |

| Sleznik | 22,5 | |

| Shelf | 0,5 | |

| Heel | 13,75–9,75 | |

| 1.2. Frieze | 9,5 | |

| 1.3. Architrave | – | |

| Shelf | 11,5 | |

| fillet | 11,5–9,5 | |

| Belt | 9,5 | |

| 2. Column | – | |

| 2.1. Capital | – | |

| Shelf | 14,5 | |

| fillet | 14,5–13,5 | |

| Abaca (tear dropper) | 13,5 | |

| Quarter shaft (echin) | 13,25–10,5 | |

| Shelf | 10,5 | |

| Neck | 9,5 | |

| 2.2. Rod (fust) | – | |

| Roller | ||

| Shelf | 0,5 | 10,5 |

| fillet | 10,5–9,5 | |

| Kernel | 9,5–12 | |

| fillet | 1,5 | 12-13,5 |

| 2.3. Column base | – | |

| Shelf | 13,5 | |

| Shaft | 16,5 | |

| Plinth | 16,5 | |

| 3. Pedestal | – | |

| 3.1. Pedestal cornice | – | |

| Shelf | 20,5 | |

| Heel | 20–17 | |

| 3.2. Chair | – | |

| Chair | 16,5 | |

| fillet | 16,5–18,5 | |

| 3.3. Pedestal base | – | |

| Shelf | 18,5 | |

| Plinth (base) | 20,5 |

Incomplete order 210 –

Full order266 –

Rice. 19. Reconstruction of the Etruscan temple-areostyle (according to Vitruvius)

- a classic example of the Etruscan order

Doric order

The second type of simple order. Vitruvius writes the following about its origin: “First of all, they (the Greeks) built the temple of Apollo Panionian…. When they wanted to place columns in this temple and, not knowing their proportionality, were looking for ways to ensure that the columns were suitable for carrying weight and retained impeccable elegance in appearance, they measured the footprint of a man’s foot and began to set this measure to the height of the person . Finding that the size of a leg was one-sixth the height of a person, they transferred this proportion to the column and the thickness of the rod at its base was set aside six times in height, including the capital. So the Doric column began to represent the proportion, strength and beauty of the male body in buildings...” (Fig. 20).

Rice. 20. Likening the Doric column to a male body: a – Kritian ephebe (Acropolis Museum, Athens); b – Doric column Propylaea (Acropolis of Athens)

By the time of Vignola, the Doric order had become much more elegant - the height of the column had increased to eight diameters. Two types of orders appeared - jagged and modular. They have slight differences in the structure of the cornice and capital. In contrast to the “ascetic” Tuscan order, additional decorations and details appeared here - flutes, denticles, modulons, triglyphs, metopes, etc. Read more about them in the Dictionary.

Tables 3 and 4 show the dimensions of the modular and gear orders according to Vignola in desks. The dimensions of the protrusions are taken from the axis of the column. For ease of figurative perception, the dimensions are written from top to bottom - from the cornice of the entablature to the base of the pedestal.

Table 3

Table 4

Doric dentate order

| Profiles | Height in desks | Protrusion from the axis in the desks |

| 1. ENTABLEMENT | – | |

| 1.1. Entablature cornice | – | |

| Shelf | ||

| fillet | 34–31 | |

| Shelf | 0,5 | 30,5 |

| heel | 1,5 | 30–29 |

| Sleznik | 28,5 | |

| Shelf | 0,5 | 15,5 |

| cloves | ||

| Shelf | 0,5 | |

| heel | 12,5–11,5 | |

| Triglyph capital | ||

| 1.2. Triglyph | 10(+0,5) | |

| 1.3. Architrave | – | |

| Shelf | 11,5 | |

| Regula | 0,5 | |

| Droplets (utes) | 1,5 | 11–10,5 |

| Belt | 8(10-2) | |

| 2.1. Capital | – | |

| Shelf | 0,5 | 15,5 |

| Heel | 15,25–14,25 | |

| Abacus | 2,5 | |

| Quarter shaft | 2,5 | 13,75–11,5 |

| Top shelf | 0,5 | 11,5 |

| Middle shelf | 0,5 | |

| Bottom shelf | 0,5 | 10,5 |

| fillet | 0,5 | 10,5–10 |

| Neck | 3,5 |

The entire illustrative part of the dentate Doric order is shown in Fig. 28–31. Here you can get acquainted with the entablature and the upper part of the column of this type of order, and in Fig. 32 - with the main varieties of denticles found in the Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders.

Rice. 28. Entablature and capital of the crenellated Doric order from Vignola’s treatise (folio XIII)

Rice. 29. Notched Doric order (entablature, capital, ceiling)

Rice. 30. Notched Doric order (entablature, capital)

Rice. 31. Notched Doric order (entablature, plafond)

Rice. 32. Teeth (denticles): a – Doric order; b – Ionic order; c – Corinthian order

Ionic order

The first type of complex order. About its origin, Vitruvius in his book “On Architecture” writes the following: “Subsequently they (the Greeks) built a temple of a new order in honor of Diana; at the same time, seeking its external difference, through the same borrowings (from man) they gave it the gracefulness of a woman: first of all, they made the thickness of the column an eighth of its height, so that it would appear taller. At the base of the column they put a base instead of a sole (foot); They attached curls to the capitals on the right and left sides, hanging down like curled curls on a hairstyle; they decorated the front side with wavy carved decorations (cymatium) arranged like waves and hanging festoons, and along the entire trunk of the column they lowered flutes, like folds on tables (robes) worn by women. Thus, they invented two different types of column: one - in appearance similar to a naked man, the other - in its decoration and proportionality, reminiscent of an elegant woman ... ".

The author of the Ionic order is known. This is the architect Khersiphron, the creator of the third “wonder of the world” - the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus (mid-6th century BC). The Greeks proclaimed this temple “the beginning of the birth of a new (Ionic) style” (Fig. 33, Fig. 34).

Rice. 33. Temple of Artemis in Ephesus (mid 6th century BC – 4th century BC). Reconstruction

With Vignola, this order became more refined compared to its ancient prototype. The diameter of the column is 1/9 of its height.

Table 5 shows the main dimensions of the Ionic order profiles (their height and projections from the column axis).

Illustrations of the Ionic order can be found in Fig. 35–37 (entablature, capital) and in Fig. 38–40 (column base, pedestal of the Ionic order).

Rice. 34. Temple of Artemis in Ephesus (mid 6th century BC – 4th century BC). Fragments

Ionic order Table 5

| Profiles | Height in desks | Protrusion from the axis in the desks |

| 1. ENTABLEMENT | – | |

| 1.1. Entablature cornice | 31,5 | – |

| Shelf | 1,5 | |

| Goose | 46–41 | |

| Shelf | 0,5 | |

| heel | 40,5–39 | |

| Sleznik | 38,5 | |

| Quarter shaft | 28,5–24,5 | |

| Roller | ||

| Shelf | 0,5 | 24,5 |

| cloves | ||

| Shelf | ||

| heel | 19,5–15,5 | |

| 1.2. Frieze (zoophore) | ||

| 1.3. Architrave | 22,5 | – |

| Shelf | 1,5 | |

| Heel | 19–17 | |

| Top lane | 7,5 | 16,5 |

| Middle lane | 15,75 | |

| Bottom Band | 4,5 | |

| 2. COLUMN | – | |

| 2.1. Capital | – | |

| Shelf | ||

| Heel | 19,5–17,75 | |

| Shelf | 17,5 | |

| Volute channel | ||

| Quarter shaft | 22–17 | |

| 2.2. Rod (fust) | – | |

| Roller | ||

| Shelf | ||

| Top fillet | 17–15 | |

| Kernel | 15–19,33–18 | |

| Bottom fillet | 1,5 | 18–20 |

| Shelf | 1,5 | |

| 2.3. Column base | – | |

| Shaft | ||

| Shelf | 0,25 | 20,5 |

| Scotia | 20,5–22 | |

| Shelf | 0,25 | 22,5 |

| Roller | ||

| Roller | ||

| Shelf | 0,25 | 22,5 |

| Scotia | 22,5–24 | |

| Shelf | 0,25 | 24,5 |

| Plinth | ||

| 3. PEDESTAL | – | |

| 3.1. Pedestal cornice | – | |

| Shelf | 0,66 | |

| heel | 1,33 | 34,5–33,5 |

| Sleznik | ||

| Quarter shaft | 29,5–26,75 | |

| Roller | 27,5 | |

| 3.2. Pedestal chair | – | |

| Shelf | 26,5 | |

| fillet | 1,25 | 26–25 |

| Chair | 84,75 | |

| fillet | 25–26 | |

| Shelf | 26,5 | |

| 3.3. Pedestal chair | – | |

| Roller | 1,33 | 27,5 |

| Reverse jib | 27–32,5 | |

| Shelf | 0,66 | 32,5 |

| Plinth |

Incomplete order 405 –

Full order 513 –

Rice. 35. Entablature and capital of the Ionic order from Vignola’s treatise (folio XVIII)

Rice. 36. Ionic order (entablature, capital)

Rice. 37. Ionic order (fragments of the entablature and ceiling)

Rice. 38. Column base and pedestal of the Ionic order from Vignola’s treatise (folio XVIII)

Rice. 39. Column base, Ionic order pedestal

Rice. 40. Column base, Ionic order pedestal

Corinthian order

The most complex, slender and light of the orders in proportions.

The legend about its origin says the following: “The third order, the so-called Corinthian, was created in imitation of maiden grace, since its more elegant decorations than in other orders give the impression of the tenderness of a maiden, who, thanks to her youth, has graceful limbs... And the creation of this capital, as they say, took place under these circumstances. One Corinthian citizen, a girl who had already reached marriageable age, became seriously ill and died. After the funeral, her nurse collected and put into a basket those trinkets that gave pleasure to this girl during her life, took them to the monument, placed them on top of it and, so that these little things remained in the open air as long as possible, covered them with a lid. This basket was accidentally placed over the root of an acanthus (acanthus). By spring, the acanthus root located in the middle, crushed by the weight, sprouted leaves and stems, and the stems, growing on the sides of the basket, crushed at the corners of the lid by the force of its gravity, willy-nilly had to make bends and curls along the edges. One day, Callimachus, nicknamed “the artist” by the Athenians for the grace and subtlety of his marble work, passed by this monument. He noticed this basket and around it tender, young leaves; touched by the peculiarity and novelty of this form, he made columns from the Corinthians based on this model and established the proportions of the Corinthian order in the construction of buildings ... ".

The Corinthian column was first used in the temple of Apollo in Bassae (region of Phegalia, Peloponnese - c. 430 BC, architect Iktin) (Fig. 44, Fig. 45).

Rice. 44. Sanctuary of the Temple of Apollo at Bassae (architect Ictinus, 430 BC). Current state

This order received further development in the architecture of Ancient Greece of the transitional and Hellenistic periods, in the architecture of Ancient Rome (Fig. 46-47).

Rule of the Five Orders of Architecture / Giacomo Barozzio da Vignola; Translation by A. G. Gabrichevsky; Comment by G. N. Emelyanov. - The publication is stereotypical. - Reprint from the 1939 edition (Moscow: Publishing House of the All-Union Academy of Architecture). - Moscow: Publishing House "Architecture-S", 2005. - 168 p., ill. - (Classics of architectural theory).

FROM THE PUBLISHER.

This edition is based on the first edition of Vignola’s treatise known to us, which most researchers date back to 1562 or 1563, based on a letter dated June 12, 1562 from Vignola’s son Giacinto, who, on behalf of his father, sent a copy of the “Rule” to Duke Ottavio Farnese in Parma, and under the privilege of Pope Pius IV, who reigned from 1559 to 1564. This edition, published without the name of the publisher and without indicating the place and year of publication, consists of 32 sheets engraved on copper, continuously numbered, including the title page (I), the papal privilege (II ) and dedication with an appeal to readers (III); the 1562 edition (based on a copy stored in the State Hermitage library) is reproduced in its entirety in this edition, occupying the title page, text introductory part and tables from IV to XXXII. However, the question of the first edition of Vignol’s treatise and its dating cannot yet be considered finally resolved. Indeed, the last paragraph of the preface to the readers, where Vignola promises to give an explication on the tables of the most commonly used architectural terms, is engraved for lack of space in a smaller font and is undoubtedly a later postscript, as well as the explications themselves and the corresponding letters on the tables, engraved in smaller font. If we add to this the existing oral evidence about the existence of an earlier, wood-engraved edition, and also if we take into account the ornamentation of the title page, which speaks in favor of a later dating, we have to admit that we are still far from a final solution to the problem. The next edition, presumably published in the 70s, i.e., possibly during Vignola’s lifetime, and also without indicating the publisher, year and place, differs from the “first” in that it adds five tables: a comparison of the five orders - table III, portals of Caprarola - table. XXXIII and XXXIV, Cancelleria - table. XXXVI, door of Palazzo Farnese - plate. XXXV and fireplace - table. XXXVII. In subsequent editions (by Rossi and Orlandi in Rome, as well as in Venice - see Bibliography) the tables of the first two are reproduced, apparently from the same boards, with the addition of a number of tables depicting the buildings of Michelangelo, of which only the Porta is included in this edition del Popolo (Plate XXXVIII), since Vignola participated in its construction. Thus, the reader has before him the complete composition of the so-called “first” edition and all the most interesting additions of the subsequent ones, and the text of the treatise, arranged in tables, is given in Russian translation in front of the tables themselves.

The text of the treatise is accompanied by translations of biographical materials about Vignola from the 16th to the 18th centuries. In the first place are excerpts from the Lives of Vasari, a contemporary of Vignola, who did not devote a separate essay to the “description” of his works, as he did for the greatest masters who lived in his time, but limited himself to brief and rather discreet mentions of Vignola in a whole series biographies. In his reviews one can often sense a rival, as, for example, in attempts to belittle Vignola’s role in the construction of the villa of Pope Julius, the composition of which Vasari attributes entirely to himself. The main source for Vignola’s biography is the biography of Vasari, written by Ignazio Danti (1537-1586) and prefaced by Vignola’s “Two Rules of Applied Perspective,” which he published with extensive commentary after the death of the master in 1583. Ignazio Danti, a major mathematician and a geographer of his time, was the son of the architect Giulio Danti, who was Vignola's assistant for a long time. The closeness of the Danti family to the Vignola family is for us a guarantee of the reliability of the information that Danti gives in his biography of the master. The following biography, borrowed from Baglione’s collection “Lives of Painters, Sculptors and Architects from 1572 to 1642,” dates back to the 17th century. and characterizes the universal recognition that Vignola’s work received in the Baroque era. And finally, the last biography of Milizia from his “Notes on the Most Famous Architects” is interesting for the critical assessments of its author, a practicing architect of the mid-18th century, a passionate champion of classicism, a strict adherent of the canons, ready to expose any “classicist” in error or liberty.

The commentary by the architect G.N. Emelyanov is the first attempt to provide a critical analysis of the Vignola canon. In numerous commented publications of the 17th and 18th centuries. for the most part this task is not even posed; usually the matter is limited to a detailed retelling and parallel comparison of Vignol's orders with the orders of other theorists. The commentary to this edition provides a critical analysis method Vignolas. In this regard, the author touches on a number of problems that are very little or not covered at all in the existing literature, namely, Vignola’s attitude towards those ancient monuments that he mentions, his attitude towards the theorists who preceded him - Vitruvius, Alberti and Serlio, the degree of his dependence on them and , finally, the question of the connection between his canon and the buildings he carried out. Attached to the commentary is a brief chronological outline of Vignola’s life and work, which lists all reliable works attributed to him, indicating the main publications containing measurements or other images of these buildings. The editors considered it necessary to limit this part to brief reference material, bearing in mind that the publication of the treatise should not at all turn into a monograph on Vignolles as an architect. Compiling a bibliography presented particular difficulties. Not to mention the fact that the issue of the first editions of the treatise has not yet been resolved; only a small fraction of the countless reprints of the treatise are represented in the book depositories of the Union. This forced the editors to abandon an exhaustive and, what would have been highly desirable, an annotated bibliography.

The introductory article and chronological outline were compiled by A. G. Gabrichevsky, who also translated the text of the treatise. Biographical materials were translated from Italian by A. I. Venediktov. The commentary was compiled by G. N. Emelyanov, bibliography by A. L. Sacchetti.

VIGNOLLA'S TREATISE AND ITS HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

Vignola's "Rule of Five Orders" was first printed in Rome in 1562. Vignola's Treatise is the last document of the Renaissance in Rome; The Church of Gesù, designed by Vignola, is the first Jesuit church, the first example of mature Baroque architecture. Vignola, as a theorist and practitioner, was brought up in the traditions of the art of the high Renaissance, in the traditions of the school of Bramante and Raphael; however, his activity as a mature master, dating back to the second and third quarter of the 16th century, already took place in an atmosphere of increasingly intensifying feudal and clerical reaction, during the years of the Council of Trent and the Jesuit Inquisition, during the years of the deep crisis of the realistic worldview, a crisis that found direct expression in the forms of the early Roman Baroque. The work of Vignola, as a master of the transitional period, had an equally strong influence on both the creation of the architectural style of the Roman Counter-Reformation and the expansion of Renaissance classics beyond the borders of Rome and even Italy.

The defeat of Rome by imperial troops in 1527 greatly bled the artistic culture of the papal capital. Many masters emigrated: some to the north of Italy, like Giulio Romano and Sansovino, some to France, like Serlio and Primaticcio, who was followed for a time by Vignola. Of the major masters in Rome, only Michelangelo remained, whose bright individuality left its mark on the Roman art of subsequent generations. Vignola, who after his death in 1564 supervised the construction of the Cathedral of St. Peter, did not escape his influence; Moreover, he, along with Michelangelo, was one of the creators of the Roman Baroque. However, having lost ground in Rome, the classical tradition of the high Renaissance did not die, but gradually and firmly conquered northern Italy (Giulio Romano in Mantua, Palladio and Sansovino in Venice, Sanmichele in Verona, Alessi in Genoa), then France, and finally the whole Europe, where this tradition, gradually degenerating, lives up to the eclecticism of the 19th century. In this process of expansion and rebirth of Roman classics, a significant role was played not only by the connection of individual masters with the traditions of antiquity or the Roman school, but also by architectural treatises, among which Vignola’s treatise occupies a very special place.

Thanks to its brevity, dogmatic presentation and simplicity of calculation methods, the “Rule of Five Orders” became the canonical textbook for almost all architectural schools that adopted the “classical” tradition of the Italian Renaissance, i.e., in other words, for almost all European architecture from the 17th to the mid-19th V. This is evidenced by countless editions and revisions of the treatise in all European languages**. With its elementaryity and practicality, this manual eclipsed Vitruvius, Serlio, Palladio, and Scamozzi, who were studied by individual specialists and major masters, but who never had and could not have the popularity and influence on everyday architectural practice that befell Vignolas. The popularity of Vignol's treatise therefore played a dual role in the history of European architecture: positive and negative. On the one hand, the “Rule of Five Orders” undoubtedly contributed to the rapid maturation and development of order architecture in various European countries, since it provided a publicly accessible key to the problems of the classical heritage***. However, on the other hand, it was precisely thanks to its elementary and dogmatic nature that the treatise became the gospel for all types of academic and eclectic formalism, especially in the 19th century. To understand the peculiar fate of this book, which, having arisen on the basis of truly classical art of the high Renaissance, turned into a dead academic “cheat sheet,” it is necessary to become somewhat more familiar with the history of its origin and the content of the treatise itself.

____________

* The exception is England, where Palladio was especially popular.

**See Bibliography at the end of the book.

*** This applies especially to France and, apparently, to Russia. Russian masters of the 18th century were undoubtedly familiar with Vignola, as evidenced by Russian editions of the treatise of that time. The question of Vignola's influence on the architectural practice of Russian classicism is a task for future research.

Even while he was in Bologna, young Vignola was apparently closely acquainted with such experts on antiquity as the architects Peruzzi and Serlio, the historian Guicciardini and the philologist Alessandro Manzuoli. In 1532, Vignola arrived in Rome, which had not yet recovered from the defeat of 1527. However, already under Paul III (Farnese), elected in 1534, cultural, construction and artistic activity began to gradually revive. Peruzzi, who returned to Rome, supervises the construction of the Vatican and takes Vignola as his assistant. Despite the reactionary policies of Paul III, under whom the Inquisition was already rampant and the Council of Trent was opened in 1535, the Counter-Reformation in the person of the pope is still tolerant of humanism, which finds many adherents among the nobility, writers and artists. The traditions of the “golden age” are still alive; moreover, the 30s and 40s were characterized by a tendency to summarize and canonize the great achievements of antiquity and the Renaissance. After the timelessness of the 20s, there is a new wave of archaeological research, a desire to understand the essence of the accomplished revival of antiquity, to understand its historical roots, and to formulate the laws of truly classical art. This tendency formed the basis of Vasari’s “Biographies,” the idea of which arose in 1546 among those writers and artists who were patronized by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, Vignola’s constant patron and customer, who dedicated his treatise to him; this same tendency formed the basis of the Vitruvian Academy, in the depths of which, undoubtedly, the idea of Vignol’s treatise matured. This academy, apparently founded in 1538, bore the loud name “Academy of Valor” (Academia della Virtú); its members included, among others, Alessandro Manzuoli from Bologna, Marcello Cervini (future Pope Marcellus II), Cardinal Maffei, philologist, The grammarian and critic Claudio Tolomei and the commentator Vitruvius Philander, as well as the architects Peruzzi and Vignola, who died in 1536, left a wealth of material on the theory and archeology of ancient architecture, which was largely used by Serlio in his treatise, the first books of which were published. already in 1537 the Academy did not exist for long; however, judging by the letter that has reached us from Claudio Tolomei to Count Agostino Landi dated November 14, 1543, the Vitruvians, following in the footsteps of Raphael, Fra Giocondo and Castiglione* set themselves grandiose tasks, which were briefly summarized to the following. Firstly, a new critical edition of Vitruvius’ text was planned, as well as a publication of the same text, presented in “good” Ciceronian Latin and equipped with drawings both illustrating the text itself and reproducing ancient buildings, indicating agreements with the Vitruvian canon and deviations. from him; in addition, an Italian translation, a dictionary of obscure expressions of the original, a dictionary of Latin and Greek technical terms, an explanatory dictionary of Italian terms and, finally, an index allowing one to find a particular term in the corresponding pictures were expected. Secondly, a historical description of all - both preserved and destroyed - ancient buildings in Rome and beyond, was conceived, as well as a monumental publication of sketches and measurements of all ancient antiquities, down to medals and all kinds of tools, and each monument was supposed to have a historical and aesthetic commentary, and a special section was given to ancient orders and details.

____________

* Wed. “Masters of Art on Art”, vol. I, pp. 163-171. M. OGIZ, 1937.

This extensive program, which was designed to last three years, remained unimplemented, in all likelihood, due to the lack of financial support from some philanthropist, the need for whose involvement is clearly hinted at by Tolomei in his letter to Count Landi. However, the work of the academicians was not in vain. Apart from the fact that Barbaro and other later theorists and commentators could use the materials of the academy, Vignola undoubtedly took part in its research from 1536 (when, after the death of Peruzzi, he lost his position in the construction of the Vatican) until his departure to France in 1541. It is equally certain, finally, that the “Rule of Five Orders” is the fruit of Vignola’s work at the Vitruvian Academy.

But Vignola was no armchair scientist. Inundated with orders and absorbed in practical activities, only twenty years later he began publishing his manual, having at his disposal extensive measuring material. This happened, as he himself says in his preface to “Readers,” at the insistence of friends. There is no doubt that all the tables of the so-called “first” edition were made by Vignola himself. This is evidenced by his original drawings stored in the Uffizi (see Chronological outline), on which Vignola even wrote the entire text in the form in which it was reproduced in the engravings. Moreover, it is possible that Vignola is also the author of the engravings; In support of this assumption, we can cite the words of Vasari (see p. 61), who in the life of Marcantonio mentions Vignola as an engraver, referring to his treatise. In addition, we should not forget that just at this time, in the early 60s, the construction of Caprarola began, and it is possible that the architect wanted to acquaint the customer, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, with the elementary laws of his art; It is not for nothing that Vignola depicted the Caprarola cornice in his treatise as an example of a cornice. From the preface it is clear that Vignola did not want to limit himself to publishing a short manual, but intended to publish a whole series of studies on the theory of architecture**, of which only his “Perspective”, published in the posthumous edition of Danti in 1583, has reached us.

____________

** According to the testimony of Vasari (see p. 62), which in this case there is no reason not to trust, Vignola, in addition to his published works - that is, obviously, the treatise - “writes” other theoretical works (Vasari wrote about Vignola, when Vignola was 58 years old, i.e. in 1565. The second edition of the Lives, in which the author included information about his contemporaries, was published in 1568).

If other theoretical works of Vignola had been preserved, the fate of his treatise would probably have been different; it is possible that a dogmatic and formal summary manual would have received the fundamental and scientific justification it lacked, which would have paralyzed the negative influence it had on European architectural practice. And most importantly, we would certainly receive an answer to a whole series of perplexities and questions that arise in every architect and historian when carefully studying the “Rule of Five Orders.”

All these questions basically boil down to the following: how can we explain that Vignola, even in a short manual, considers the order as a completely abstract system, without connecting it in any way with problems of scale and absolute size? How can we explain that Vignola does not say a word about the mutual dependence of the height of the column, its narrowing and the size of the intercolumns, at least within the limits of what Vitruvius gives and which Vignola, of course, could not help but know? What is the average, optimal order height that Vignola based his system of proportions on? He could not believe that these proportions are suitable for any absolute value and that they can be mechanically increased or decreased without distorting their meaning, as apparently all those “classics” and eclectics who honestly built according to Vignola thought. To assume that the “Rule of Five Orders” is nothing more than a short guide for masons and sculptors is hardly possible, if you believe the author, who in the preface directly says that his canon is the fruit of many years of scientific research and was developed by him “exclusively to use it for my own needs." Finally, it is enough to at least approximately estimate Vignola’s “Rule” to his own buildings that have come down to us, and we will easily be convinced that Vignola the architect, with the possible exception of the cornice in Caprarola and the partially unpreserved and measured house of Letarui in Piazza Navona, not only “freely” applies his “Rule”, but most often he does not take it into account at all. There is no doubt that Vignola the artist in practice always proceeded from those large-scale patterns that Vignola the theorist did not utter a single word about.

True, one phrase in the preface sheds some light on this problem. Objecting to those who do not believe in the possibility of unshakable rules, they refer to Vitruvius, who argued that “in decorations we constantly have to increase or decrease the proportions of individual divisions in order, with the help of art, to compensate for what our vision is deceived for one or another random reason.” , Vignola replies: “In such cases, it is still necessary to know exactly what size our eye should see, and this will always be the firm rule that is considered necessary to observe *.” In addition, one must use certain and excellent rules of perspective...” Despite some vagueness of Vignola’s expressions, from this phrase we can conclude, firstly, that in Vignola’s time there were anti-classical, already baroque, movements in architectural theory and practice that used Vitruvius to deny the very possibility of a rational justification of the laws of architecture**, in secondly, that Vignola is precisely a supporter of this pattern, extending its action to those optical adjustments that Vitruvius speaks of and which relate to the field of perspective - a science, in his opinion, necessary for an architect no less than a painter. True, “Two Rules of Practical Perspective”, published after Vignola’s death, relate exclusively to descriptive perspective and do not give anything on the issue of taking into account perspective perception when creating architectural forms; nevertheless, we repeat, Vignola could not help but know about those laws of scale that about which he is silent in his treatise and which, undoubtedly, should have been covered in other treatises that were not written by him or that have not reached us. The question of why he did not consider it necessary to touch upon them in his short manual remains open. Without resorting to the unlikely hypothesis of professional secrecy in this case, we have to admit that Vignola was a very bad teacher, unaware of the harm that he would bring to many, many generations of architects.

____________

* I quote a very unclear Italian text of this phrase, the translation of which I do not at all feel confident in: “in questo caso esser in ogni modo necessario sapere quanto si vuole che appaia all'occhio nostro, il che sara sempre la regola ferma che altri si havera proposto di osservare."

It is not for nothing that Wölfflin (“Renaissance und Barock.” 3 Aufl., S. 11), apparently based on the same phrase, draws a diametrically opposite conclusion, with which, given our understanding of the text, it is impossible to agree: “In everything that goes beyond warrants, he considers himself not bound by anything. He doesn’t care about the spirit of antiquity.”

** Characteristically, the information that has reached us is that in 1541 the “Academy of Wrath” (Academia dello Sdegno) was founded in Rome to combat Vitruvianism and the Vitruvian Academy. Wed. Atangi, Lettere facete, 1601, pp. 374, 377, see Promis, Architetti ed architettura presso i Romani; p. 66 - Memorie della Reale Academia delle Scienze di Torino, Serie seconda, tomo 27, Torino 1873.

However, if the formalism and abstractness in the concept of the treatise do not give us any right to talk about the formalism of Vignola as a theorist in general, and even more so about the formalism of Vignola as an artist, nevertheless, in the very method of constructing his order canon, Vignola is still, in any case, an eclecticist in in comparison with Vitruvius and Alberti, as well as in comparison with Palladio and the northern Italian theorists of the 16th century, who adopted the realistic tradition of antiquity and the 15th century. This realistic tradition is characterized, on the one hand, by a concrete rather than abstract understanding of the order, the proportions of which are always established in connection with the actual dimensions of the building as a whole, its design features and the visual conditions of its perception; on the other hand, Italian theorists who adopted this tradition are characterized by a realistic attitude towards the ancient heritage; so, for example, both Alberti and Palladio are very liberal in relation to the canon, or rather, they do not so much establish a certain canon how much do they give samples, allowing countless options and countless deviations depending on the specific conditions that determine the structure of the artistic image; Moreover, Palladio, giving the normal proportions of a particular order, usually gives measurements specific ancient monument, as the most beautiful and satisfying example. That's not what Vignola does. If we do not have sufficient materials to completely accuse Vignola’s entire architectural aesthetics of formalism, especially since his artistic creativity does not allow us to do this, then with regard to his use of the ancient heritage in the construction of the order, we are dealing with a peculiar type of eclectic construction of a certain an abstract system that is created on the basis of Vitruvius and other theorists and by selecting and abstracting individual features from the entire set of ancient monuments. In this regard, Vignola’s “orders”, in the form in which they are presented in his treatise, essentially have little in common with specific examples of ancient art and, in any case, in spirit are incomparably further from antiquity than, for example, the examples of Palladio, although both rely on Vitruvius and approximately the same circle of Roman monuments. To be convinced of this, it is enough to carefully read the preface to “Readers”, where Vignola covers his method in detail. First of all, Vignola proceeds from the aesthetic axiom that those works that “have certain definitions and less complex numerical relationships and proportions” seem more beautiful, and those in which “every smallest division serves exactly as a unit of measurement for larger divisions,” i.e. i.e. those for whom the modular principle of integers is not only a method approximate numerical expression of quantities, but also the principle of real construction. In other words, Vignola deliberately simplifies and vulgarizes all the richness and variety of often irrational relationships observed in most ancient works. Further, Vignola, composing his canonical samples, however, selects, in his words, some specific concrete example, but subjects it to a peculiar treatment of a purely eclectic order: “If any smallest division is not entirely subordinate to the proportions of numbers (which is very often the case in the work of stonemasons or stems from any other accidents that are of great importance for such trifles), I level this out in my rule, without, however, allowing any significant deviations, but relying in such small liberties on the authority of other buildings.” This is how we get purely abstract, prepared “ideas” of the five orders.

So, the Vignolian canon has, in essence, very little in common with antiquity; it is rather a canon of the late Roman Renaissance, a canon created in connection with the tendency to retroactively summarize and record the achievements of the “golden age”. We have already talked about this tendency - it is typical of the crisis of the realistic worldview that occurred in Rome on the basis of feudal and clerical reaction. At the same time, the assumption involuntarily arises that Vignola, although giving a rebuke to anti-classical tendencies in architecture, already has one foot on the soil of the Baroque, for which the order gradually loses its real constructive meaning and more and more acquires the character of an abstract and, essentially, already a decorative system.

The conclusions for the Soviet architect suggest themselves. Vignola's treatise is a highly interesting document, as a fragment of the extensive theoretical and archaeological research of the greatest master that has not reached us, and as an attempt to canonize the architectural forms of antiquity on the border between the Renaissance and the Baroque. It is possible to fully understand and appreciate Vignola’s experience only in connection with the general history of the development of theoretical thought and in connection with the study of Vignola’s work as an architect, which is the task of future research, after all the surviving buildings of the master have been examined and measured, and after how it will be established to what extent and how Vignola himself used the canon he established in his architectural practice. At the same time, the “Rule of Five Orders” in no case can and should not serve as either a teaching aid or a design guide; it should not at all bind our architect in his creative work, just as it did not bind Vignola himself in this regard. However, no architect can ignore Vignola if he wants to understand the history of the classical heritage in European architecture, from the Renaissance to the present day. At the same time, the study of Vignola can be of benefit to a student or architect only under the condition of a purely critical attitude towards him, under the condition of a preliminary study of specific examples of the classics and, finally, under the condition of a deep knowledge, at least according to Vitruvius and Palladio, of all those problems of classical architecture, about which Vignola is silent.

A. Gabrichevsky.

From the publisher... 5

Vignola's treatise and its historical significance - A. Gabrichevsky. 7

Vignola - Rule of five orders. Per. A. Gabrichevsky... 11

Vasari, Danti, Baglione, Milizia - Lives of Vignola. Per. A. Venediktova 59

The construction of orders in masses is a simplified image of them, in which small details are excluded, and all curved lines are conditionally replaced by straight ones (Fig. 2, 3).

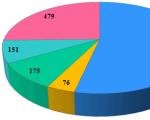

Due to the fact that the basic proportions of the composite order are the same as the Corinthian, and in terms of the richness of decoration and originality it differs little from the Ionic and Corinthian, four orders are subject to detailed analysis - Tuscan, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian (Fig. 1).

All parts of the order have certain sizes, which are in strict mutual relation. Architects have been searching for the correct relationship between the height of a column and an entablature for many centuries. By studying these dimensions from surviving ancient buildings, the Renaissance theorist Vignola derived some average simple ratios that have become generally accepted.

According to Vignola, the height of the entablature is 1/4, and the height of the pedestal is 1/3 of the height of the column. Therefore, to determine the main parts of the order, it is necessary to divide its entire height into 3 unequal parts, proportional to 1/4:1:1/3 or 3:12:4 (bringing the fractions to a common denominator). Adding these parts, we get 19, i.e. dividing the entire height into 19 parts, 3 upper parts are separated into entablature; 12 middle parts – on the column and 4 lower ones - on pedestal.

Let us consider separately each part included in the order. When comparing those presented in table. 1 of the four orders in the masses it is clear that the Tuscan column differs from other types of columns in its greater massiveness and heaviness of proportions. Its thickness is equal to 1/7 of the height. The thickness of the Doric column is slightly smaller and equal to 1/8 of the height, the Ionic - 1/9, the Corinthian - 1/10.

Since all parts of the order depend on each other in size, there is no place for absolute values such as meter, centimeter.

In each individual case, some part of the order must be taken as a unit of measure. The lower radius of the column was considered such a part and this measure was called MODULE. To display the small details of the order, the module is divided into parts called PARTS; in the Tuscan and Doric orders there are 12, and in the Ionic and Corinthian orders there are 18 parts.

Having understood what a module is and using the data in Table 1, which shows the sizes of the main parts of the order in modules, you can continue building orders in masses.

Table 1

Construction of architectural orders among the masses

The column is a round pillar, somewhat thinning at the top.

This thinning is 1/6 of the lower thickness of the column and usually begins with one third of its height, while the lower third of the column is made cylindrical. Thus, the upper diameter of the column is 5/6 of the lower diameter. When drawing a column on a small scale, the thinning part is shown with slightly slanted lines. On a large scale, thinning is done along a smooth curve called ENTHASIS.

Having outlined the main middle part of the column, called the ROD or TRUNK, you can move on to building its lower part - the BASE, and then the upper part - the CAPITAL.

Height bases for all orders is equal to one module. The base consists of two parts: the lower part - a square plate - PLINT - makes up the base of the base; the upper part is a RING, round in plan, - the transition from the column rod to the plinth (Fig. 2).

In the Tuscan and Doric orders, the ring and plinth are equal in size and the ring in the masses is depicted by an inclined line, expanding downwards at an angle of 45 °, In the Ionic and Corinthian orders, the ring is 2/3 of the height of the base and its downward expansion is shown at an angle of 60°.

The top part of the column is called the CAPITAL.

The height of the capitals of the Tuscan and Doric orders, like bases, is equal to one module. The capital consists of three parts of equal width. The upper part is a square plate – ABAKA; middle – round in plan in the form of a half-shaft – EKHIN; the lower one is a continuation of the column rod - NECK. Dividing the height of the capital into three equal parts, the neck should be considered as a continuation of the column rod; Echinus is shown as an oblique line, widening upward at an angle of 45°; The abacus is depicted by a vertical line directly from the inclined echinus.

The capital of the Ionic order has special spiral curls - VOLUTES and is very different from other capitals. It has an abacus and a shaft, no neck, and the height of the capital is 2/3 of the module. Its construction among the masses is carried out as follows. The total size of the capital is set aside - 2/3 of the module, and then the abacus - 1/6 of the module. On the bottom line of the capital - at a distance of I module from the axis of the column - there are centers of volutes. Conventionally, volutes are depicted as a rectangle. In this case, the values for the distance of the sides of the rectangle from the center of the volute are observed: vertically up - 9 desks, down - 7 desks; horizontally further from the axis of the column - 8 desks, closer to the axis - 6 desks. With a very small modulus, it is permissible to depict volutes in the shape of a square with a side equal to one modulus (Fig. 4a).

The height of the Corinthian capital is 2 and 1/3 modules; 1/3 of the module falls on the abacus and 2 modules on the rest of the capital, which has a complex treatment in the form of two rows of leaves and curls growing from them. The width of the abacus is three modules. After laying 11/2 modules to one side or the other from the axis from the fixed points, the columns are made inclined at an angle of 45° to the axis until they intersect with the bottom line of the abacus, and then continue until they connect with the top of the column trunk (Fig. 4,b) .

Fig.4 Capitals in masses: a) ionic; b) Corinthian

Moving on to the construction of the entablature, it is necessary to remember the RULE OF HANGING, which consists in the fact that the upper parts of the architectural elements should not be wider than the lower ones, i.e. on any image of a corner column, the vertical line of the entablature angle must correspond to the continuation of the outline of the column trunk. Those architectural parts that, for special reasons, have extensions at the top should not bear any load (overhanging part of the cornice).

The entablature consists of three parts: ARCHITRASP, FRIEZE AND CARNICE.

The architrave is the first significant part of the entablature, which consists of horizontal beams that cover the space between the columns. In the first two orders, the architraves have a very simple shape and their size is equal to 1 module. In the Ionic order, this form is divided into three stripes and ends with a profile at the top. The height of the architrave has been increased accordingly – up to 1 and 1/4 modules.

In the Corinthian order, the architrave was further developed and has a height of 1 and 1/2 modules. Considering that in all orders there are protruding elements in the upper part of the architrave, conventionally, when depicting this part of the order in masses, the architrave line slightly expands upward. Above the architrave is the middle part of the entablature - the frieze. For all four orders, the frieze is shown by a vertical line coinciding with the line of continuation of the column trunk. The size of the frieze is carried out according to the data given in Table 1.

Above the frieze is the upper part of the entablature - the cornice.

This is one of the most important architectural forms, having an expansion at the top, which is explained by the special purpose of the cornice of the order or building. If the wall of the building ended smoothly at the top, without any protruding parts, and the roof did not directly begin, then dust, along with atmospheric moisture, would flow from the roof along the walls of the building. To avoid this, stone slabs are laid at the top of the wall, protruding forward from the plane of the walls, and the roof begins from these slabs. Such protruding stone slabs constitute the HANGING PART OF THE CORNICE (Fig. 5). Thanks to the hanging eaves slabs, water from the roof flows down the outer vertical plane of these slabs, at some distance from the wall. However, due to the properties of water, some of the liquid blown by the wind may fall on the wall. To prevent this from happening, a recess is made in the lower surface of the hanging stone slab. Drops of water, having reached the recess in the slab, cannot rise up and drip down like tears. This similarity was the reason for giving the groove in the stone the name TEARCHER, and the stone itself being called TEARSTONE.

Fig.5 Elements of cornice

The desire to push this overhanging part forward as much as possible and ensure its balance led to a device for widening the wall under the tear stones, which was called the SUPPORTING PART OF THE CARNICE.

To protect the outer surface of the teardrop stone, brightly illuminated by the sun, from water leaks, the part of the roof located directly on the teardrop is made in the form of an artistically processed gutter. This part of the cornice is called the CROWNING part. It is usually decorated with lion heads and ornaments.

Thus, the cornice consists of three parts: supporting, protruding and crowning. The size of each part of the cornice is indicated in the table. When constructing in masses, the projection of the cornice is conventionally assumed to be equal to its width, so that the most protruding point is determined by drawing an inclined line at an angle of 45° from the bottom of the cornice. The middle part of the cornice projects forward, having an overhang in the form of a horizontal straight line, constituting the lower part of the tear stone.

The depiction of pedestals is not difficult and is not described in detail. You just need to remember that the bases are very important structural parts of the order and the width of the pedestal should be equal to the width of the lower part of the column base.

Having studied all four orders in their main features or in masses, further study of them should follow the path of considering individual details.

All rules given in this section are set out according to the Giacomo Vignola system (unless specifically stated otherwise).

In ancient Greek architecture, three orders emerged: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. Later, two more were created: Tuscan (simple) in Rome, and complex (composite) in the Renaissance.

What is an architectural order

Architectural order- this is the order of arrangement of the structural parts of a structure, in which the rational distribution and interaction of the carrying and load-bearing parts received a certain figurative expression (form) that corresponds to the practical (utilitarian) and artistic purpose of the structure.

The order arose on the material basis of the post-and-beam structure and became its artistic expression. The main elements of the order are the column and the architrave ceiling. They perform a practical function, providing shelter from rain and sun; they are structural elements that form a sustainable construction system, and finally. They perform an artistic function, creating one or another artistic image of the building.

That is, the order system is constructive and at the same time artistic.

Orders and order systems received their highest development in ancient Greece in the VI-III centuries. BC in temples and public buildings built of stone. But elements of the order began to take shape in adobe-wood architecture that was more ancient than stone, which has not reached us. The structures and forms developed in wood were then turned into stone, modified under the influence of new materials and new methods of processing and designing them. In ancient Greece, three main orders were developed: Doric, Ionic and Corinthian.

Later, during the Renaissance, the architectural order began to be understood as a collection of rules formulated by Vitruvius in his treatise “On Architecture”. But, since not a single drawing has survived and this work contains many gaps regarding the proportions of various parts of the order, several interpretations arose from different Renaissance authors.

The most widespread interpretations are those of Andrea Palladio and Vignola. The rules formulated by these architects can still be applied now; they are transparent, easy to remember and understandable.

The proportions of orders have never been a strict canon and have varied throughout the history of architecture. The proportions given here are taken from Vignola from the book of Augustus Garneri “Orders of Civil Architecture” and from the book by I.B. Mikhailovsky "Theory of classical architectural forms".

Limitation of the use of the order system

The canonical order systems, created by theoretician and practical architects and reflecting centuries-old construction experience, despite all their clarity and regularity, do not answer many questions and are to some extent abstract schemes that ignore many specific construction conditions.

In these systems, the real scale is almost not taken into account, the connection between the order and the building itself and its surroundings is not understood, and the material is not taken into account; assigning a specific intercolumnium size to each type of order is conditional and abstract.

But one must understand the true meaning of this system and the limits of its use. Classical architects did not consider the canonical order system as a collection of unchangeable rules and ready-made architectural forms and techniques that could only be borrowed and applied in practice. They believed that, based on the canonical system, order and order compositions need to be solved specifically, looking for their specific proportions and forms depending on the purpose of the building, compositional idea, scale, structures, environment, etc.

Articles

- Brief historical overview (Ikonnikov A.V.)

Development of the architectural order as an artistic and constructive system

Excerpt from the book: Ikonnikov A.V. “The artistic language of architecture” M.: Art, 1985, ill.

To complete the task, you must select one of the orders. The required elements of the drawing must be arranged on a sheet using architectural drawing composition techniques (all elements used must belong to the same order). The work is done with a pencil and drawing tools.

The main task: to correctly convey all the details, their proportions and relative positions of elements, spatial relative positions using linear graphics.

The work is performed on a stretcher measuring 55 * 75 cm.

On the subframe you need to arrange:

1. Full order with intercolumnium.

2. Part of the order.

3. Order profile (bummers).

4. Order name.

5. Details.

Procedure for completing the task

1. Working with analogues, studying the rules for constructing an order.

2. Selecting image scales.

3. Layout of drawings on a subframe. Approval of sheet composition.

4. Carrying out the entire volume of work (main projections and details) in thin lines with a pencil and tools.

5. Identifying plans. Outlining drawings. Working out the details.

6. Shutdown.

LITERATURE

1. Rules of five orders. Vignola. - M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Architecture, 1940. - 186 p.

2. Vitruvius. Ten books about architecture. - M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Architecture, 1936. - 255 p.

3. Fundamentals of architectural composition. Ikonnikov A.V., Stepanov G.P. -M.: Art, 1971. - 223 p.

4. Mikhalkovsky I. B. Theory of classical architectural forms. - M.: Higher School, 1940. - 240 p.

5. Palladio. Four books about architecture. - M.: Publishing House of the Academy of Architecture, 1936. - 142 p.

APPENDIX 1

SAMPLES OF STUDENT WORK

APPENDIX 2

ORDER CONSTRUCTION TABLES

Building an order in the masses

Types of orders

a) Doric order

b) Tuscan order

c) Ionic order

d) Corinthian order

e) Composite order

Composition of orders

Architectural orders among the masses

Architectural orders among the masses

Comparative analysis of Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders in Greek and Roman architecture

APPENDIX 3

ARCHITECTURAL ORDERS AND NAMES OF DETAILS OF ARCHITECTURAL MOLDING DECORATION

ARCHITECTURAL ORDERS

The proportions of the complete order are as follows: if the height is divided into 19 equal parts, then the height of the pedestal will be four parts, the columns - 12 parts and the entablature - three parts. An incomplete order is divided into five parts: four parts are a column, one part is an entablature (architrave, frieze, cornice).

Depending on the form, architectural orders are distinguished: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian. In addition to the listed orders, there is a composite order, which has additions that are not present in the classical order (masks, griffins, garlands, etc.) on the capitals of the columns.

The scale of all parts of the order is the radius of the column at its lower base. This radius is called a module and is designated by the letter M. In the Tuscan and Doric orders, the module is divided into 12 parts, and in the Ionic and Corinthian orders - into 18. These parts are called desks and are designated by the letter P. The cores of the columns of all orders are round.

Tuscan the order has massive parts. The column is smooth, its height is equal to 7 lower diameters, or 14 modules. At 1/3 of the height the column is flat, and above it it thins to the capital at 1/5 of the lower diameter. The column ends with a simple round capital. The frieze and architrave are smooth. Such an order is often finished entirely by plasterers; sometimes the capital is prepared by molders and installed after finishing the column.

Doric the order is less massive than the Tuscan one. A column with a height equal to 8 diameters, or 16 modules, can be smooth or with 20 flutes (grooves). The flutes are separated from each other by sharp appendages, rounded at the top and bottom. The depth of the flutes is determined by the project. At l/3 of the height the column has a constant cross-section; above it it thins by 1/6 of the lower diameter. The column is crowned with a capital with smaller architectural breaks than the Tuscan capital. The architrave is smooth at the base and has a shelf at the top with drops located below. On the smooth frieze there are triglyphs - three even stripes separated by triangular notches. The spaces between the triglyphs are called methods. They can be smooth or with images made from various materials. Decorations in the form of cloves, crackers and modulons are made under the cornice. Such orders are either completely executed by plasterers, or triglyphs, crackers and modulons, and sometimes capitals are executed by sculptors.

Tuscan order

Doric order